Public Health Scotland

Child and Family Training (C&FT) is a not-for-profit organisation that aims to help professionals help children and families

In this Research Practice Focus video, from UK Trauma Council ACEs are explained, shown how they are measured, and the pros and cons of routine screening.

References (Introduction)

Dube S (2020). Twenty years and counting – the past, present and future of ACEs Research, in G. Asmundsen and T Afifie (eds). Adverse Childhood experiences. Academic Press.

Felitti V.J. Anda R.J et al (1998). Child Abuse and Household dysfunction and adverse health impact ACE. Am J Preventitive Med, 14: 245-258.

McLaughlin K et al (2016). Maltreatment Exposure, and the long shadow of adverse childhood experiences. Psychological Science Agenda.

Vizard, E., Gray, J., & Bentovim, A. (2021). The impact of child maltreatment on the mental and physical health of child victims: A review of the evidence. BJPsych Advances, 1-11. doi:10.1192/bja.2021.10.

References (What we already know)

Baldwin J et al (2020). Population vs Individual prediction of poor health from results of Adverse Childhood Screening. JAMA Paediatrics, 10.1001/5602.

Baumeister, D., Akhtar, R., Pariante C.M., Mondelli, V. (2016) Childhood trauma and adulthood inflammation: a meta-analysis of peripheral C-reactive protein, interleukin-6 and tumour necrosis factor-α. Mol Psychiatry, 21, 642 – 649

Bellis MA, Hardcastle K, Ford K, et al (2017) Does continuous trusted adult support in childhood impart life-course resilience against adverse child- hood experiences – a retrospective study on adult health-harming behaviours and mental well-being. BMC Psychiatry, 17, 1, 110.

Bellis, M. A., Hughes, K., Ford, K., Rodriguez, G. M., Sethi, D., & Passmore, J. (2019). Life course health consequences and associated annual costs of adverse childhood experiences across Europe and North America; a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Public Health, 4(10), e517–528. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/S2468-2667(19)30145-8.

Bellis, M. A., Hughes, K., Ford, K., Hardcastle, K. A., Sharp, C. A., Wood, S., … Davies, A. (2018). Adverse childhood experiences and sources of childhood resilience: A retrospective study of their combined relationships with child health and educational attendance. BMC Public Health, 18, 792

Bevilaqua, L., Kelly ,Y. Heilman, A., Priest, N. Lacey, R. (2021) Adverse childhood experiences and trajectories of internalising and externalising, and prosocial behaviours from childhood to adolescence Child Abuse and Neglect 112. 104890

Cecil, C.A.M., Viding, E., Fearon, P., Glaser, D., & McCrory, E.J. (2017). Disentangling the mental health of childhood abuse and neglect. Child Abuse and Neglect, 63, 106-119.

Conti G, Morris S, Melnychuk M, et al (2017) The Economic Costs of Child Maltreatment in the UK: A Preliminary Study. NSPCC.

Danese A, Pariante CM, Caspi A, et al (2007) Childhood maltreatment predicts adult inflammation in a life-course study. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 104 (4): 1319-24.

Danese A, McEwan BS (2012) Adverse Childhood Experiences, allostasis, allostatic load, and age-related disease. Physiology and Behavior, 106 (1): 29-39.

Fang X, Brown D.S., Florence C.S. and Mercy ,J.A. (2012) The economic burden of child-maltreatment in the United States and implications for prevention Child Abuse and Neglect 36, 156 – 165

Fritz J., de Graaff A.M. Caisley ,H. van Harmelen, A .Wilkinson P.Q. (2018) A Systematic Review of Amenable Resilience Factors That Moderate and/or Mediate the Relationship Between Childhood Adversity and Mental Health in Young People3.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00230/full?report=reader

Gondek, D., Patalay P, Lacey R.E (2021) Adverse childhood experiences and multiple mental health outcomes through adult a prospective birth cohort study J. Public Health , https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdy0992018

Gentry, S.V. Paterson, B.A., (202), Does screening or routine enquiry for adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) meet criteria for a screening programme? A rapid evidence summary, Journal of Public Health, fdab238, https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdab238

Henry L.M., Gracey K., Shaffer A. et al (2021) Comparison of Three Models of Adverse Childhood Experiences: Associations With Child and Adolescent Internalizing and Externalizing Symptoms Journal of Abnormal Psychology 130 , 9 -2

Hughes K, Bellis MA et al (2017). The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Public Health 2: 356–366.

Hughes, K., Ford, K., Bellis, M.A., Glendinning, F., Harrison, E., Passmore, J. (2021) Health and financial costs of adverse childhood experiences in 28 European countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis The Lancet – Public health, 6 e848- e857

Kuhlman, K. R., Horn, S. R., Chiang, J. J., & Bower, J. E. (2020). Early life adversity exposure and circulating markers of inflammation in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 86, 30-42

Lacey R & Minnis H (2019). Practitioner Review: Twenty years of research with adverse childhood experience scores – Advantages, disadvantages and applications to practice. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 61(2), 116–130.

Lacey R. Pinto Pereira S.M, Danese A., (2020) Adverse childhood experiences and adult inflammation: -Single adversity, cumulative risk and latent class approaches. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity 87 820–830

Latham R.M., Meehan A.J., 2019 Arseneault, L, Danese A., Fisher, H.L (2019 ) Development of an individualised risk calculator for poor functioning in young people victimised in childhood: a longitudinal cohort study Child Abuse and Neglect 98 104188

Lewis, S.J., Arseneault, L, Caspi, A., Fisher, H.L., Mathews, T., Moffitt, T., & Danese, A. (2019). The epidemiology of trauma and post-traumatic stress disorder in a representative cohort of young people in England and Wales. Lancet Psychiatry, 6, 247 – 256.

Lewis S. et al (2021) Unravelling the contribution of complex trauma to psychopathology and cognitive deficits: a cohort study. BJPsych 2021 419-455

McCrory, E., Gerin, M. I., & Viding, E. (2017). Child maltreatment. Latent vulnerability, and the shift to preventative psychiatry – The contribution of functional brain imaging. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 58, 338–357.

Meehan AJ et al (2020). Developing an individualised risk calculator for psychopathology among young people victimised during childhood: a population- representative cohort study, J Affective Disorders 262 90 -98.

Meehan A.J. , Baldwin ,J. Lewis, S.L. Macleod J.G., Danese A. (2021) Poor Individual Risk Classification from Adverse Childhood Experiences Screening Am J. Prev. Med. Doi:10.1016?jamepre.2021.08.008

National Scientific Council on the Developing Child (2008/2012) Establishing a Level Foundation for Life: Mental Health Begins in Early Childhood (Working Paper No. 6) (Updated Edition). Center on the Developing Child, Harvard University.

Nelson B.W, Sheeber L., Pfeifer J. Allen N.B 2021 psychobiological markers of allostatic load in depressed and non-depressed mothers and their adolescent offspring Journal Child Psychology & Psychiatry 62, 199 -211

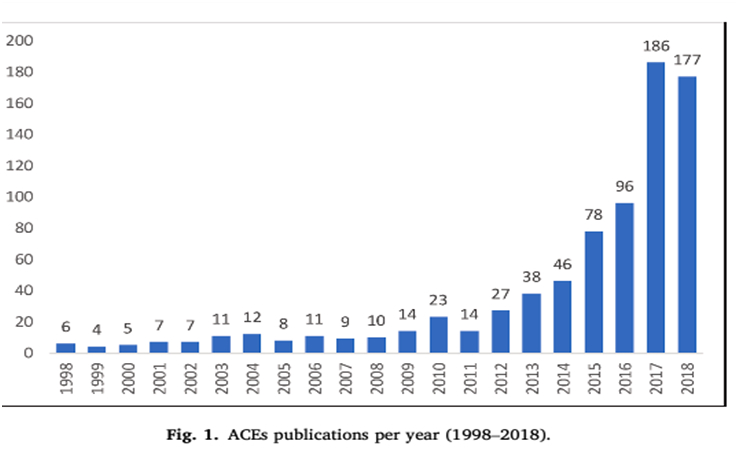

Struck S, Syewart-Tufesco A et al (2021). Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) research: A bibliometric analysis of publication trends over the first 20 years. CAN 112: 104895

Teicher, M. H., Samson, J. A., Anderson, C. M., & Ohashi, K. (2016). The effects of childhood maltreatment on brain structure, function and connectivity. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 17, 652–666. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn.2016.111.

Thompson, R., Litrownik, A.J., Isbell, P., Everson, M.D., English, D.J., Dubowitz, H., Proctor, L.J., & Flaherty, E.G. (2012). Adverse experiences and suicidal ideation in adolescence: Exploring the link using the LONGSCAN samples Psychology of Violence, 2(2), 211-225. doi: 10.1037/a0027107.

Vizard, E., Gray, J., & Bentovim, A. (2021). The impact of child maltreatment on the mental and physical health of child victims: A review of the evidence. BJPsych Advances, 1-11. doi:10.1192/bja.2021.10

Available from: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/bjpsych-advances/article/impact-of-child-maltreatment-on-the-mental-and-physical-health-of-child-victims-a-review-of-the-evidence/D5A662192092FADD5E9F594B65C083FA/share/bf4f35a8cd7c6f7fbd92ed4bf8c44e8c13b88247

References (Areas of Uncertainty)

Finkelhor, D., Omrod, R. K., & Turner, H. A. (2007). Poly-victimisation: A neglected component in child victimization. Child Abuse and Neglect, 31, 7–26.

Radford, L., Corral, S., Bradley, C., et al. (2011). Child abuse and neglect in the UK Today. London: NSPCC. https://learning.nspcc.org.uk/media/1042/child-abuse-neglect-uk-today-research-report.pdf

Van IJzendoorn, M. H., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., Coughlan, B., & Reijman, S. (2020). Differential susceptibility perspective on risk and resilience. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 61(3), 272–290.

References (Applications)

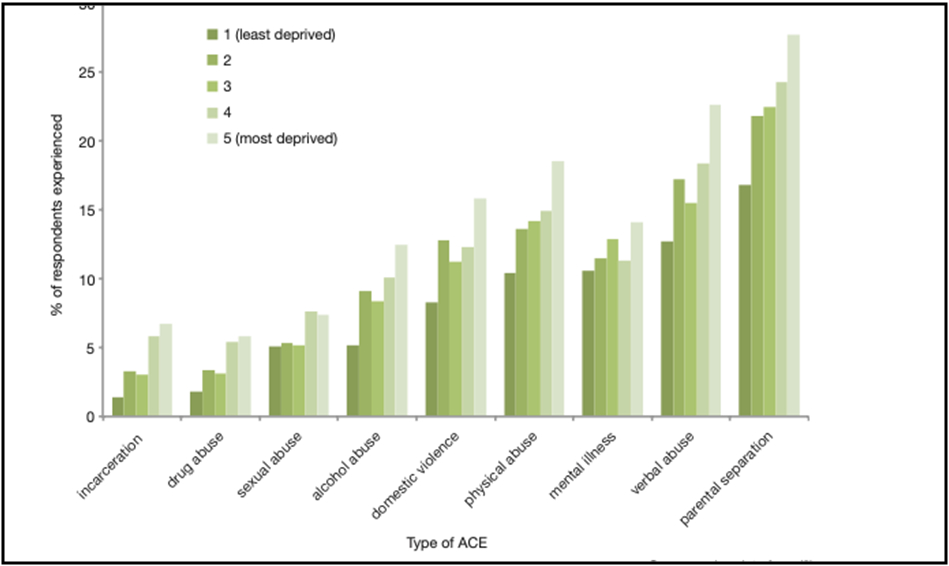

Allen M & Donkin A (2015) The impact of adverse experiencesin the home on the health of children and young people, and inequalities in prevalence and effects. Institute of health equity: London, UCL.

Asmussen K., Fischer F., Drayton E. et al. (2020). Adverse childhood experiences. What we know, what we don’t know, and what should happen next. London: Early Intervention Foundation.

Asmussen K and McBride T (20210 Adverse Childhood Experiences – Building Consensus – What Happens Next. London; Early Intervention Foundation.

Bendall S, Eastwood O, Cox G et al. (2021) A systematic review and synthesis of trauma-informed care within outpatient and counseling health settings for young people. Child Maltreat 2020;1077559520927468. (2nd July 2021, date last accessed).

Bentovim, A., Cox, A., Bingley Miller, L. and Pizzey, S. 2009. Safeguarding Children Living with Trauma and Family Violence: A Guide to Evidence-Based Assessment, Analysis and Planning Interventions. London: Jessica Kingsley.

Bentovim A (2017a). Promoting children and young people’s health, development and wellbeing. In A Bentovim & J Gray (eds.). Hope for Children and Families: Building on strengths, overcoming difficulties. York, UK: Child and Family Training.

Bentovim A (2017b). Modifying abusive and neglectful parenting. In A Bentovim & J Gray (eds.). Hope for Children and Families: Building on strengths, overcoming difficulties. York, UK: Child and Family Training.

Cox, A. & Bentovim, A. (2000). The Family Pack of Questionnaires and Scales. London:The Stationery Office.

Cox, A., Pizzey, S. & Walker, S. (2009). The HOME Inventory: A Guide for Practitioners – The UK Approach. York, UK: Child and Family Training.

Cox, A. & Walker, S. (2002). The HOME Inventory: A Training Approach for the UK. Brighton: Pavillion.

Bentovim A, Chorpita BF et al (2020). The value of a modular, multi-focal, trauma-informed therapeutic approach to preventing child maltreatment: hope for children and families intervention resources. A disruptive innovation. Child Abuse & Neglect 119:104703.

Bentovim A & Gray J (eds.) (2016; 2017; 2018). Hope for children and families: Building on strengths, overcoming difficulties. York, UK: Child and Family Training.

Bentovim A, Gray J, Heasman P & Pizzey S (2017). Engagement and goal setting. In A Bentovim & J Gray (eds.). Hope for Children and Families: Building on strengths, overcoming difficulties. York, UK: Child and Family Training.

Caldwell, B. M. and Bradley, R. H. (2001) Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment: Administration Manual (3rd edition). Arkansas: University of Arkansas.

Cecil, C.A.M., Viding, E., Fearon, P., Glaser, D., & McCrory, E.J. (2017). Disentangling the mental health of childhood abuse and neglect. Child Abuse and Neglect, 63, 106-119.

Chorpita BF & Daleiden EL (2009). Mapping evidence-based treatments for children and adolescents: Application of the distillation and matching model to 615 treatments from 322 randomized trials. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77(3): 566–579.

Chorpita BF & Weisz JR (2009). Modular approach to children with anxiety, depression, trauma and conduct Match-ADTC. Satellite Beach FL: PracticeWise LCC.

Chorpita BF, Daleiden EL & Weisz JR (2005). Identifying and selecting the common elements of evidence based interventions: A distillation and matching model. Mental Health Services Research, 7: 5–20.

Chorpita, B. F., Daleiden, E. L., Park, A. L., Ward, A. M., Levy, M. C., Cromley, T., … Krull, J. L. (2017). Child STEPs in California: A cluster randomized effectiveness trial comparing modular treatment with community implemented treatment for youth with anxiety, depression, conduct problems, or traumatic stress. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 85(1), 13–25.

Cox, A. & Bentovim, A. (2000). The Family Pack of Questionnaires and Scales. London:The Stationery Office.

Cox, A., Pizzey, S. & Walker, S. (2009). The HOME Inventory: A Guide for Practitioners – The UK Approach. York, UK: Child and Family Training.

Cox, A. & Walker, S. (2002). The HOME Inventory: A Training Approach for the UK. Brighton: Pavillion.

Department of Health, Department for Education and Employment, & Home Office (2000). The framework for the assessment of children in need and their families. London, UK: The Stationery Office.

Eldridge H (2017). Working with children and young people: Addressing disruptive behaviour. In A Bentovim & J Gray (eds.). Hope for Children and Families: Building on strengths, overcoming difficulties. York, UK: Child and Family Training.

Gates C & Peters J (2017). Promoting attachment, attuned responsiveness and positive emotional relationships. In A Bentovim & J Gray (eds.). Hope for Children and Families: Building on strengths, overcoming difficulties. York, UK: Child and Family Training.

Marie-Mitchell A & Kostolansky R. (2019). A systematic review of trials to improve child outcomes associated with adverse childhood experiences. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 56(5): 756–764.

Macdonald, G., Lewis, J., Ghate, D., Gardner, E., Adams, C. & Kelly, K. (2017). Evaluation of the Safeguarding Children Assessment and Analysis Framework (SAAF). London: Department for Education.

Macdonald G, Livingstone N et al (2016). The effectiveness, acceptability and cost-effectiveness of psychosocial interventions for maltreated children and adolescents: An evidence synthesis. Health Technology Assessment, 20(69), 1–508.

McCrory, E., Gerin, M. I., & Viding, E. (2017). Child maltreatment. Latent vulnerability, and the shift to preventative psychiatry – The contribution of functional brain imaging. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 58, 338–357.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2017). NICE guideline. Child abuse and neglect.

NHS Highlands (2018). Adverse childhood experiences, resilience and trauma informed care: A public health approach to understanding and responding to adversity. Annual Report of the Director of Public Health 2018, NHS Highland.

Pachter, L., Lieberman, L., Bloom, S., & Fein, J.A. (2017). Developing a Community-Wide Initiative to Address Childhood Adversity and Toxic Stress: A Case Study of The Philadelphia ACE Task Force. Academic Pediatrics, 17(7), S130–S135.

Pizzey, S., Bentovim, A., Cox, A., Bingley Miller, L. and Tapp, S. (2016). The Safeguarding Children Assessment and Analysis Framework. York: Child and Family Training.

Prinz, R. J., Sanders, M. R., Shapiro, C. J., Whitaker, D. J., & Lutzker, J. R. (2009). Population-based prevention of maltreatment. Prevention Science, 10, 1–12.

Radford, L., Corral, S., Bradley, C., et al. (2011). Child abuse and neglect in the UK Today. London: NSPCC.

Roberts R (2016). Promoting positive parenting. In A Bentovim & J Gray (eds.). Hope for Children and Families: Building on strengths, overcoming difficulties. York, UK: Child and Family Training.

Walsh MC, Joyce S, Maloney T, Vaithianathan R. (2020) Exploring the protective factors of children and families identified at highest risk of adverse childhood experiences by a predictive risk model: an analysis of the growing up in New Zealand cohort. Child Youth Serv Rev 1;108:104556.

Weeramanthri T (2016). Working with children and young people: Addressing emotional and traumatic responses. In A Bentovim & J Gray (eds.). Hope for Children and Families: Building on strengths, overcoming difficulties. York, UK: Child and Family Training.

References (Adverse Childhood Experiences, Adverse Community Environments, climate change, the pandemic, the internet and refugee asylum seekers)

Afifi T et al (2017). Spanking and adult mental health impairment: The case for the designation of spanking as an adverse childhood experience. Child Abuse & Neglect, 71: 24–31.

Allen M and Donkin A (2015). The impact of adverse experiences in the home on the health of children and young people, and inequalities in prevalence and effects. Institute of health Equity, UCL.

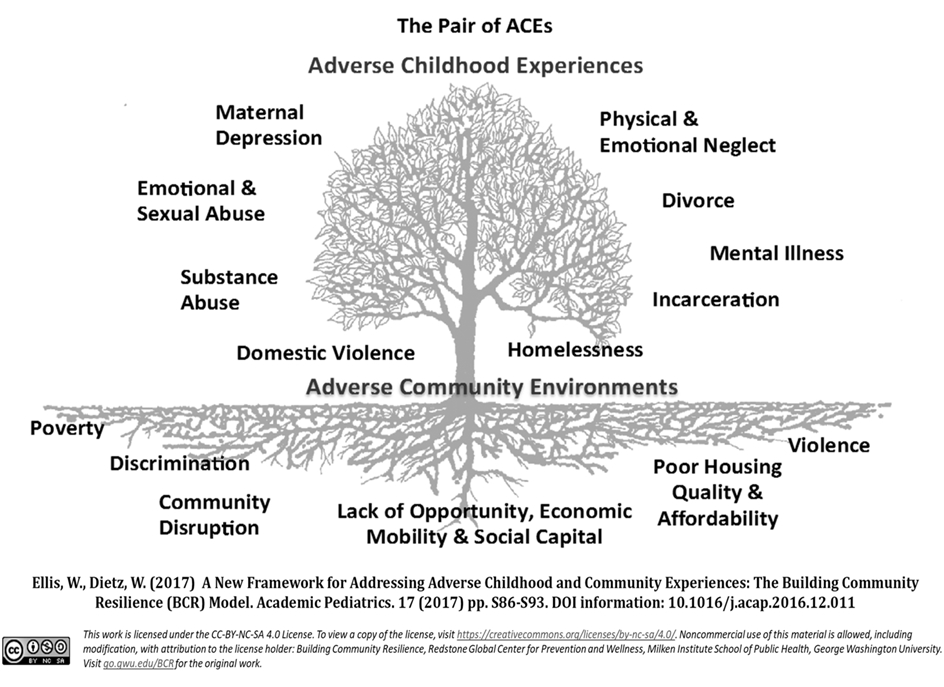

Ellis, W.R., & Deitz, W.H. (2017). A new framework for Addressing Adverse Childhood and Community Experience: The building Community Resilience Model. Academic Pediatrics, 17(7S), S86-S93.

Ford T et al (2021). Recent studies of health disorders in children and young people during the pandemic. BMJ 372: n614.

Lawrence E et al (2021). The impact of climate change on mental health and emotional well-being, implications for policy and practice. Institute of global health innovation – Grantham Institute.

NHS Digital (2021). Mental health of Children and Young People in England

NSPCC (2020). Protecting children from online abuse (last updated 23 Dec 2020). NSPCC Learning.

Wood S, Ford K, Hardcastle K, Hopkins J, Hughes K and Bellis M (2020) ACEs in child refugee and asylum-seeking populations. Public Health Wales.

Vizard, E., Gray, J., & Bentovim, A. (2021). The impact of child maltreatment on the mental and physical health of child victims: A review of the evidence. BJPsych Advances, 1-11. doi:10.1192/bja.2021.10

von Werthern M, Grigorakis G, Vizard E (2019) The mental health and wellbeing of unaccompanied refugee minors (URMs). Child Abuse and Neglect, 98: 104–46.

References (Studying ACEs in Childhood Directly)

Afifi T et al (2017) Spanking and adult mental health impairment: The case for the designation of spanking as an adverse childhood experience. Child Abuse & Neglect, 71 (2017)

Baglivio MT, Epps N et al (2014). The Prevalence of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) in the Lives of Juvenile Offenders. Journal of Juvenile Justice, 3(2): 1–23.

Brassard MR, Hart SN, Glaser D, et al (2020) Psychological maltreatment: an international challenge to children’s safety and well being. Child Abuse & Neglect, 110(Pt 1): 104611.

Carbone IT et al (2021). Childhood adversity, Suicidality and Non-Suicidal Self-Injury among children and adolescents admitted to emergency departments. Ann Epidemiol: 33932570

Craiga J.M., Piquerob A.R, Farrington, D.P. Ttofic M.M., (20170 Adverse childhood experiences and life-course offending in the Cambridge study. Journal of Criminal Justice 2017 53 34 -45

Dierkhising CB et al (2013). Trauma histories among justice involved youth. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 4: 20274

Dierkhising CB et al (2019). Developmental timing of polyvictimisation. Continuity, change and association with adverse outcomes in adolescence. Child Abuse and Neglect, 87: 40 -50

Finkelhor D, Shattuck A (2012). Improving the adverse childhood experiences study scale. American Journal of Preventative Medicine, 167, 70–75.

Flaherty, E.G., Thompson, R., Dubowitz, H., Harvey, E.M., English, D.J., Everson, M., Proctor, L.J., & Runyan, D.K. (2013) Adverse childhood experiences and child health in early adolescence. JAMA Pediatrics, 167(7), 622–629

Ford T et al (2021). Recent studies of health disorders in children and young people during the pandemic. BMJ, 372: n614.

Hibbard R, Barlow J, McMillan H, et al (2020) Clinical report: psycho- logical maltreatment. Pediatrics, 130: 372–8.

Lehman S, Breivik K et al (2020). Potentially traumatic events in foster youth, and association with DSM-5 trauma and stressor related symptoms. Child Abuse and Neglect 101: 104374.

Mars B et al (2019) Predictors of future suicide attempt among adolescents with suicidal thoughts or non-suicidal self-harm: a population-based birth cohort study Lancet Psychiatry 6 327 – 339

Thompson, R., Litrownik, A.J., Isbell, P., Everson, M.D., English, D.J., Dubowitz, H., Proctor, L.J., & Flaherty, E.G. (2012). Adverse experiences and suicidal ideation in adolescence: Exploring the link using the LONGSCAN samples. Psychology of Violence, 2(2), 211-225. doi: 10.1037/a0027107.

Turner H, Finkelhor D (2020). Strengthening the predictive power of screening for adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) in younger and older children. Child Abuse and Neglect 107: 104522/

Wood S, Ford K et al (2020). ACEs in child refugee and asylum -seeking populations 2020. Public Health Wales.

van Ijzendoorn MH, Bakermans-Kraneburg MJ, Duschinsky R, et al (2020b) Institutionalisation and deinstitutionalization of children 1: a systematic and integrative review of evidence regarding effects on development. Lancet Psychiatry, 7: 703–20.

Vizard E (2013) Practitioner Review: the victims and juvenile perpetrators of child sexual abuse – assessment and intervention. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 54: 503–15.