Young people have better access to the internet than ever before, with those under 18 accounting for one in three internet users globally (UNICEF, 2017). Digital technology use can bring opportunities of learning and connectedness in young people, and some positive experiences in relation to their mental health including access to peer support and immediacy of information and help (Pretorius et al., 2019). Additionally, young people report improved self-esteem, identity development, and sense of belonging related to using social technologies including social media and gaming (Charmaraman et al., 2018).

Despite this, there are concerns of risk associated with online use. For example, research has shown links between online activity and an increase in accessibility to harmful or distressing images, online sexual exploitation and cyberbullying (Centre for Mental Health Report, 2018). Further, concerns have been raised about potential dangers related to the influence of social media on disordered eating, self-harm, and suicidal thoughts and behaviours (Dane & Bhatia, 2023; Biddle et al., 2018). Additionally, negative online experiences have been significantly associated with increased anxiety levels (Rifkin-Zybutz et al.,).

Recently, The Royal College of the Psychiatrists in the UK advised that social media and online use should be considered in assessing risk of all young people they meet (RCPsych Report CR225, 2020). However, it is currently unclear whether this advice has been implemented in practice. Additionally, there is little evidence of guidance on how to approach these conversations with young people, or of similar direction for other mental health practitioners, teachers or parents.

What do we know?

We know MHPs and young people think that talking about young people’s online use related to their mental health is important (Rifkin-Zybutz et al., 2023).

Despite this, through focus groups and interviews with MHPs and young people (aged 16-24 yrs), Derges et al (2023) found that conversations around online activities rarely happened, and when they did, young people expressed feelings of stigma and judgment.

This study also revealed that practitioners lacked confidence in having these discussions. Both MHPs and young people indicated that improved guidance and training on the topic for MHPs could prove beneficial.

How can we improve guidance and training for MHPs having these discussions with children and young people?

As a first step in developing guidance for practitioners, a Delphi study was conducted by Biddle et al (2022).

- A Delphi study aims to gain a consensus on views, from consulting experts using questionnaires or surveys.

This Delphi study aimed to create good practice indicators (GPIs) to support MHPs when engaging young people in conversations about their online use related to their mental health.

A total of n=22 young people, and n=21 mental health practitioners were sent questionnaires, where they were asked open-ended questions, and to rank statements related to good practice. Following iterative analysis, further questionnaires were sent across two more rounds where experts were asked to again rank statements. GPIs were included where they had 75% agreement across both panels.

In total, twenty-seven GPIs were agreed by experts, covering ‘who’ should be asked and ‘when’, ‘how’ they should be asked, ‘what’ should be discussed, and what the consequence or ‘outcome’ of discussions should be. A selection of the resulting GPIs are displayed below, and all the GPIs can be at www.digital-chats.com.

Example GPIs

| Who/When? | All young people attending a mental health consultation should be asked about their online activities |

| How? | Discussion about online activities should be started spontaneously as part of the flow of conversation, with questions naturally embedded within broader topics rather than as a standalone item |

| What? | Discussions about worrying online activity should usually include asking for the names of sites visited, descriptions of content created by the young person and details of participation in online groups |

| Outcome | A clinician should not simply recommend stopping online activities but support the young person to engage with the online world in a more positive way |

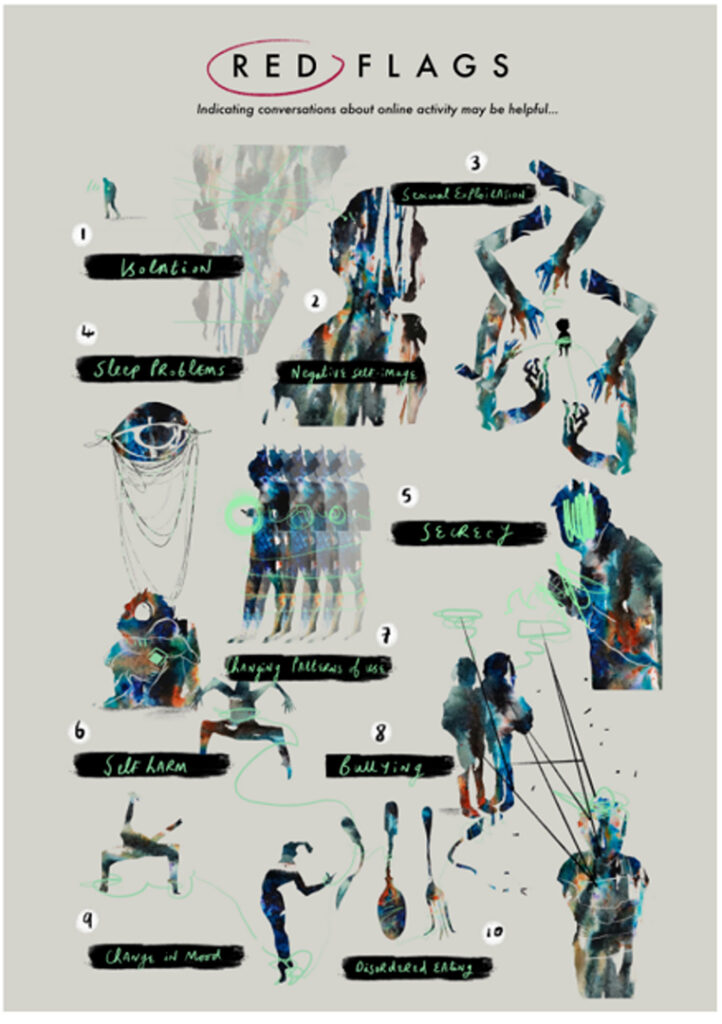

Additionally, a list of ‘red flags’, or warning signs in young people were established, to indicate when these conversations should be prioritised

What next?

Following the creation of the GPIs, researchers at the University of Bristol are hoping to create training and resources to aid MHPs in having these conversations with children and young people.

The ‘Digital Dialogues’ project aims to break down the communication barriers between MHPs and young people by co-creating and disseminating knowledge exchange resources. The project will use a variety of methods to identify the gaps in knowledge and guidance for MHPs, and work together with young people to design, produce, and share resources that can help address these .

If you are a mental health practitioner, currently working with and young people in the UK or Ireland, you can help!

The first step in the Digital Dialogues is a survey which aims to gather insights into the current practices employed by MHPs when asking young people about their online activities in relation to their mental health. Additionally, we are seeking to identify any specific preferences or needs MHPs have concerning potential training and resources to be developed as part of this project. The survey is open and can be accessed here: https://www.surveymonkey.co.uk/r/S2MVN3H

We would also like to invite MHPs currently working with children and young people in the UK and Ireland to take part in a focus group, to help us identify resources that would support you in having conversations with young people about the online world’s impact on their mental health. The focus groups will include MHPs from diverse professional backgrounds, and you will receive £10 for participating. You will have the chance to share any specific knowledge or insights you would like to gain about young people’s experiences with the online world and its influences on their mental health. By exploring your experiences and ideas, we aim to create resources that are both meaningful and helpful to MHPs.

If you’d like to participate in a focus group, let us know by expressing your interest here: https://meded.onlinesurveys.ac.uk/focus-group-sign-up

Young people will also be central to the success of the project, playing an active role in the decision-making , such as content of the resources that will be made as part of our Digital Dialogues Young Persons . The Digital Dialogues Young Persons Group will be held online, if you are a young person who wants more information about the group, please contact Zoë at zoe.haime@bristol.ac.uk. We hope that we can encourage the young people to bring their talents and creative abilities to the role, contributing to our resource discussion and production work with art, film, writing, acting, editing, storytelling, and other creative skills.

Conclusions

Digital Dialogues aims to bring together the voices of MHPs and young people to co-create resources that will ultimately aid conversations around young people’s online use and their mental .

As the Digital Dialogues project progresses, we hope to keep the ACAMH community up-to-date with our work as we go, so look out for more from us via the ACAMH channels. Additionally, in the future, we hope to share the resources we create as part of the project.

To keep up-to-date with the latest study news, give us a follow on Twitter @DgtlDialogues

Conflicts of Interest

Zoë Haime wrote this blog and currently works on the Digital Dialogues project. Zoë works closely with Lucy Biddle, who is leading the Digital Dialogues work, and has worked with Jane Derges – both of whom are cited in this piece.

References

Biddle, L. A., Rifkin-Zybutz, R. P., Derges, J., Turner, N. L., Bould, H. E., Sedgewick, F., Gooberman-Hill, R., Moran, P. A., & Linton, M-J. (2022). Developing good practice indicators to assist mental health practitioners to converse with young people about their online activities and impact on mental health: a two-panel mixed-methods Delphi study. BMC Psychiatry, 22, 485.

Biddle, L., Derges, J., Goldsmith, C., Donovan, J. L., & Gunnell, D. (2018). Using the internet for suicide-related purposes: Contrasting findings from young people in the community and self-harm patients admitted to hospital. PloS One, 13, 5, e0197712.

Centre for Mental Health. (2018). Briefing 53: social media, young people and mental health. URL: https://www.centreformentalhealth.org.uk/publications/briefing-53-social-media-young-people-and-mental-health.

Charmaraman, L., Gladstone, T., & Richer, A. (2018). Positive and negative associations between adolescents mental health and technology. Technology and Adolescent Mental Health, pp. 61-71.

Dane, A., & Bhatia, K. (2023). A social media diet: A scoping review to investigate the association between social media, body image and eating disorders amongst young people. PLoS Glob Public Health, 22, 3, e0001091.

Derges, J., Bould, H. E., Gooberman-Hill, R., Moran, P. A., Linton, M-J., Rifkin-Zybutz, R. P., & Biddle, L. A. (2023). Mental Health Practitioners’ and Young People’s Experiences of Talking about Social Media During Mental Health Consultations: Qualitative Focus Group and Interview Study. JMIR Formative Research, 7, e43115.

Pretorius, C., Chambers, D., & Coyle, D. (2019). Young people’s online help-seeking and mental health difficulties: systematic narrative review. J Med Internet Res, 21 (11), e13873.

RCPsych Report CR225. (2020). Technology use and the mental health of children and young people. RCPsych: London, UK.

Rifkin-Zybutz, R. P., Turner, N. L., Derges, J., Bould, H. E., Sedgewick, F., Gooberman-Hill, R., Linton, M-J., Moran, P. A., & Biddle, L. A. (2023). Digital Technology Use and Mental Health Consultations: Survey of the Views and Experiences of Clinicians and Young People. JMIR Mental Health, 10, e33064.

UNICEF. (2017). The State of the World’s Children: Children in a Digital World. UNICEF Division of Communication: New York, USA.